Growing up, we had numerous modes of transportation: horses, feet, driving and bikes. I learnt to drive when I was 12 – my older sister taught me how. She also tried to teach me how to ride a motorbike, but that didn’t go as well.

We weren’t allowed to drive any vehicle except Grampa’s truck which had a big leather front seat, long gear stick and wide steering wheel that felt quite thin in our hands. It smelled like dust and years of hard work. It took a while for my driving abilities to get to a speed that warranted third gear or higher, and up and down the farm road, bumping along on the bouncy seat, stretching our feet to reach the pedals, keeping within the boundaries of where we were permitted to drive, we would roar – leaving dust in our wake.

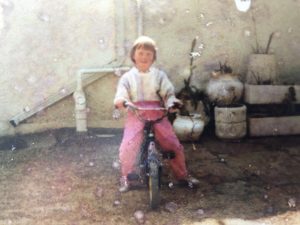

When we weren’t driving illegally, we were riding our bikes. My sister’s was a pink BMX, a gift from Father Christmas when we were just starting to figure him out (because honestly, how did he fit it in our small Jetmaster chimney?). It had tassels and a white seat. The white handles were moulded perfectly for the rider’s hands, ribbed with soft rubber, and I was so happy that she’d received it because it meant the blue one would become mine.

Blue had long padded pieces of waterproof canvas wrapped around the front handlebar and the frame with Velcro – which could be taken off and washed when it was time to play car wash – but were mostly as dirty as the roads they were ridden on. It had quite thick tires, and dad taught us how to oil our chains so that when we took them to the workshop for a service we could be mechanics without needing any assistance.

We went everywhere on our bikes, fashioned a way to hold one of mom’s baskets on the front so that we could pack picnics for when we went fishing at the dam like Tom Sawyer. Although, I’m not sure Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn used biltong hooks at the end of a line of string tied to their fishing poles. It was no wonder we never caught any fish, and the reason we needed to pack food from home.

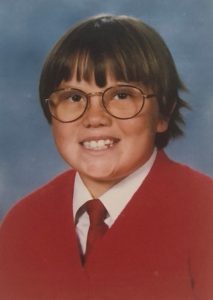

Later, when we had grown out of our pinks and blues, the bikes were passed down to the next sibling, and my older sister used the black one (technically mom’s) which was the only one with gears. This made cycling up the hill before the turn in to our driveway slightly easier, and the rider of this bike was usually the one in charge of the games – because the black bike was always ridden by the eldest.

We knew the dirt roads on our farm and around our house without being conscious of it – a map etched into our beings. The rough parts, like corrugated iron, where you lifted your feet up and bounced – sometimes singing so that you could hear your voice wobble. The very sandy sections where you dared not get caught going too slowly or you’d get stuck. The smooth sections with only light gravel that burned your bare feet in the Summer or made the worst grazes on your skin that mom would patch up with monkey blood – that’s what we called the red mercurochrome – if you fell there. And the man-made speed bumps, created with a grader to divert rain water off the road, which were ramped over – standing up and bending our legs as we flew with ease.

Fearless, we held competitions to see who could go down the hill the fastest and end up the furthest without pedalling. The corner at the bottom of the hill which lead to the workshop and old house was an added challenge to our made-up Olympic sport.

“ok, this time we stick our feet out”, we panted as we pushed our bikes back up the hill to start again.

And down we would go, helmetless, barefoot. Feet out to avoid the pedals cutting into our shins.

Screaming with joy.

The adjustable seats of all the bikes saw much use over the years. We learnt tricks without realising they were tricks – an old favourite was to make a dust wave when you slammed on breaks and let the back wheel slide out to the side. And when the training wheels were on because baby sister was learning how to ride a bike they made a really fun mud fountain – something we discovered by parking the bike over a big puddle outside the ram shed with the back wheel suspended in the water. Holding the breaks down we pedalled as fast as we could and sent the mud flying up behind us. We each took turns and the spectator was responsible for lending additional support to the front of the bike to prevent it from moving.

It was our favourite puddle, and the ram shed had a ramp which was perfect for driving down and right through the middle of it to create a tidal wave. This puddle of mud was endlessly fun, until we arrived at home one day covered in it from head to toe and mom, angry, made us hand wash our clothes which had been bought for us that very day.

“They were supposed to be town clothes!” said mom.

Mine was a white T-shirt with navy anchors on, with a pair of matching navy shorts.

Beautiful.

…And full of mud.

We giggled while we washed our clothes in the bath, badly, with a giant green bar of sunlight soap, our punishment for running out of the house before changing.

“Let’s go back tomorrow” my sister whispered.